Mollusks, which include snails, slugs, mussels, and octopuses, represent one of the most diverse animal groups on Earth today. This is certainly true for aforementioned organisms that form one of the two main branches of the mollusk evolutionary tree, but not for the other branch, the Aculifera, within which morphology has largely remained unchanged over time.

In an article led by Mark Sutton of the Imperial College, London, UK and published today in Nature, we identified two new fossil species dating back 430 million years that challenge this view. These two species named Punk ferox and Emo vorticaudum in reference to their numerous spines giving them a look reminiscent of these musical styles, document a previously unknown morphological and ecological diversity within the Aculifera.

The phylum Mollusca (e.g., snails, slugs, mussels, squid, octopuses, and chitons) is one of the most diverse groups of animals on Earth, yet lots of unknowns remain regarding their early evolution. This is mostly due to the fact that the molluscs living today represent only a fraction of the vast diversity that once existed, and that, aside from shelly remains, fully preserved fossils of these otherwise highly decay-prone organisms are extremely rare, which strongly complicates our understanding of their evolutionary history. One of the most elusive aspects of molluscan evolution lies in the history of the Aculifera, one of the two primary branches of the molluscan tree of life. Living aculiferans include the polyplacophorans (commonly known as chitons or coat-of-mail shells), which resemble eight-shelled limpets, and the relatively obscure aplacophorans—bizarre, shell-less molluscan worms. The prevailing view is that the morphology of aculiferans has remained largely unchanged over time—a pattern that stands in contrast to the considerable variability observed in other molluscs.

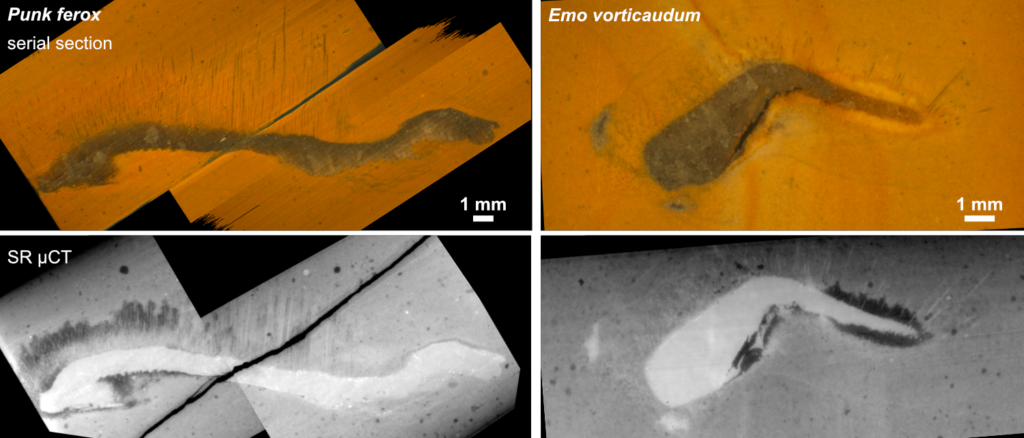

One of the few sites that has yielded fully preserved fossils of early aculiferans is the Herefordshire Lagerstätte, a fossil deposit from the Silurian period (approximately 430 million years ago) that preserves a diverse marine fauna in extraordinary detail, with organisms encased as calcitic void infills within carbonate concretions. Organisms are preserved in three-dimensions with many soft tissues remains, and have so far been reconstructed and studied digitally as ‘virtual fossils’ using serial-grinding. Two of the most complete fossil aculiferans known have been previously described from this deposit, and additional specimens were actively searched for.

Following discussions with Derek Briggs when he visited for my PhD defense at the end of October 2014, I teamed up with him, Mark Sutton and Derek and David Siveter to apply synchrotron phase-contrast X-ray microtomography to non-destructively investigate, for the first time, previously unexamined Herefordshire concretions. To the team’s delight, two new species of aculiferans were identified during the analysis of the data collected at the PSICHÉ beamline of the SOLEIL synchrotron in May 2016. The contrast obtained with synchrotron X-ray microtomography is different but complementary to that obtained from serial-griding, meaning that this technique can be applied to investigate non-destructively more Herefordshire concretions in the future.

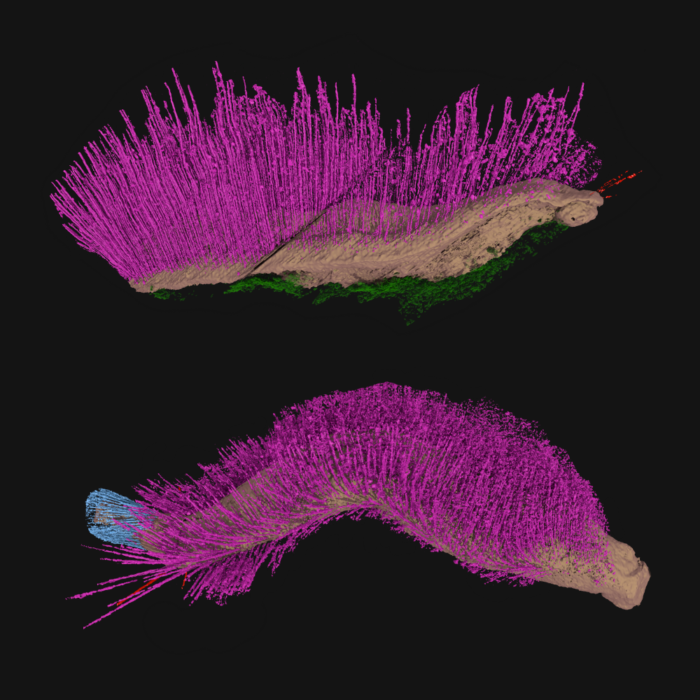

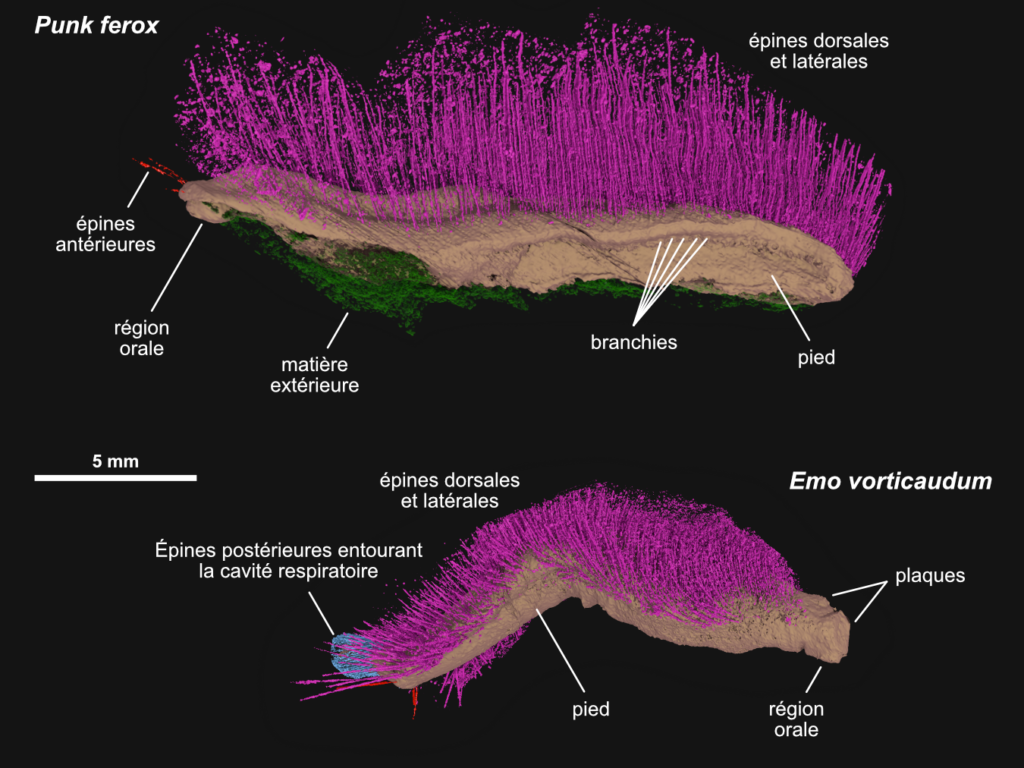

The anatomy of the two fossils was thoroughly studied and described after painstaking virtual reconstruction and dissection. Both are generally worm-like, with numerous spines that extend upward and outward, and a smooth, spine-free underside used for movement. However, aside from these similarities, they differ significantly—not only from the two previously discovered species but also from each other. One is named Punk ferox for its distinctive spiky ‘hairstyle’, and the other is called Emo vorticaudum and has two stud-like shells on its upper surface, shorter spines that form a fringe-like pattern, and a tail encircled by spirally twisted spines. These combinations of traits are entirely unique. For example, the rear end of Emo closely resembles that of some modern aplacophorans, though its shells and sole morphology fall outside the typical characteristics of that group. Punk, on the other hand, shares some features with modern polyplacophorans, yet completely lacks shells. Moreover, Emo is preserved in a posture suggesting it may have moved by ‘inching’—a mode of locomotion resembling caterpillar movement, which has never been observed in any other mollusc.

The discovery of Punk and Emo reveals that early aculiferans were no more conservative in their morphology and ecology than any other molluscan group, with living species representing only a small fraction of a once-diverse group with a complex evolutionary history.

Reference: Sutton M.D., Sigwart J.D., Briggs D.E.G., Gueriau P., King A., Siveter D.J. & Siveter D.J. 2025. New Silurian aculiferan fossils reveal complex early history of Mollusca. Nature. Find the article (Open Access) here